Lineage and the Elephant

Thoughts on when we meet our teachers

Mela Berger came to San Diego this past month and together we visited our mentor in Structural Integration, Edward Maupin. Mela’s company and conversation opened me up to become more aware of what I learned from Ed as his apprentice and what I learn from and teach to others in the present. To clearly define my rolfing practice I have to consider those parts that are the seeds that were given to me and those aspects that are the vines that grew from them. In this entry I am going to look at the idea of lineage and what it means to the students of a teacher across the duration of that teacher’s life.

Concurrent with my interest in bodywork was my zeal for taiji chuan. I’d spent years travelling prior to this moment in my life, and my only constant companions were a torn-up school bag, a ragged blanket, and a copy of Victor Mair’s translation of the Tao Te Ching. When I discovered taiji, I realized that there was a way to embody the philosophy of the Tao, to feel and express it through the fundamental experience of being in my body, to learn it from the inside out. Beyond this, I considered the practice of taiji my experimental ground for testing the claims made by the teachers I encountered at massage school. I also made considerable efforts to find the teachers who had the most experience. It was thus I began looking for “the Master.”

Through a series of teachers I began to learn of their connection to the past of taiji, the schools and lines of transmission. Each of them could trace a line of contact back into the past, and because I was primarily focused on the Yang family style, ultimately to Yang Chengfu. In his own time Yang was known as a naturally talented and rigorously trained boxer and it is he that established the fame of the Yang family name. While there are several other styles that stake a claim to the history of taiji, the most practiced forms in China and the US alike come from the Yang family due its association with the emperor in pre-revolutionary times. This association is entirely due to Yang Chengfu’s skill and promotion of the art.

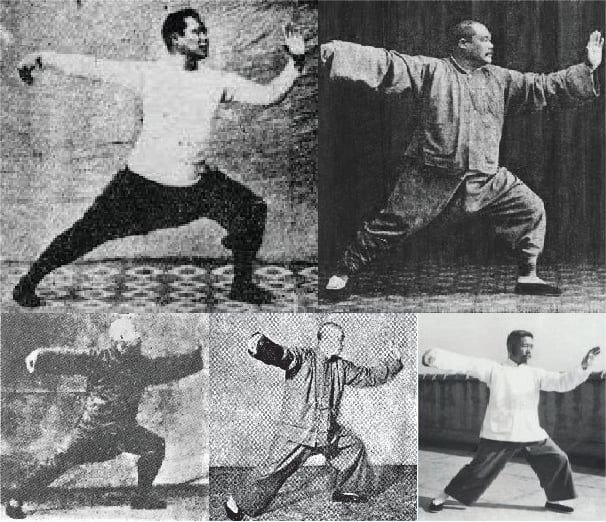

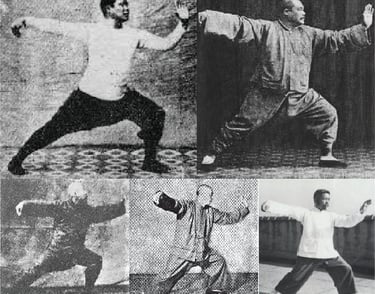

It was my teacher Abraham Liu (who studied with Cheng Man-ch’ing, who studied with Yang Chengfu) who first drew my attention to the changes that a master will go through in their life of practice. In the image above there are two large pictures of Yang Chengfu, one from his early life and teaching and one from the later part, left and right respectively. Abraham used to have these two pictures on his wall, and he would point out that as Yang learned more about the essence of taiji, his frame both softened and became more upright at the same time, embodying ‘sung’, or relaxed and present awareness. Abraham focused on this difference as a lesson in patience and perseverance, as well as a guide towards correct form.

The three images below those of Grandmaster Yang Chengfu are of his students, Chen Weiming, Tung Ying-chieh, and Cheng Man-ch’ing, left to right respectively. Because I had spent so much time finding teachers who had other lineages I was aware of Chen Weiming’s influence on Yang’s own son and the subsequent influence on the Yang style forms as practiced in China today. I also practiced at times in the park near a class of one of Tung Ying-chieh’s lineage. Chen’s tendency was that of long straight arms and legs, whereas Tung’s line practiced a form that looked bent over and closed inward. Both of these lines came from verified masters personally trained by Yang. Cheng Man-ch’ing’s line was the first to gain widespread attention in the USA, and was the form I was most closely familiar with. Also a recognized master in his own lifetime, his form focuses closely on slow movements embodying relaxation and expansion in movement. At the time, I was mystified by the differences between the styles of people who supposedly practiced not only the same art, but learned from the same teacher only 100 hundred years prior.

There is a well-worn parable of several blind men tasked to describe an elephant, a creature which they have never seen, where each touches a different part of the elephant and describes the entirety of the elephant based on the single part they have contact with (the tusk, tail, trunk, flank, ear, etc.). The story is often used to show that we tend to define a thing by the nature of our exposure to it, and also tend to exclude information from other equally true and similarly limited points of view. The story’s illustration extends not only to our appreciation of things in space, but also to how our understanding of reality changes over time.

I grouped the photos above to highlight the order in which the students learned taiji from Yang Chengfu. Earliest was Chen Weiming, as his form demonstrates. The more rigid martial stature is visible in both the early Yang and Chen in this image. Tung was somewhere in between, while Cheng learned later in Yang’s life, and his focus on softness and relaxation reflect this. This is not to say that Chen’s appreciation of taiji was less than that of Cheng’s, however, they are certainly different. Indeed, in the early stage of Yang’s practice he was much more concerned with winning bouts than he was later after having secured his family’s reputation. The time at which the student learns from the master determines the relative importance of aspects of the art they seek to attain. Lineage alone does not determine what one learns from a teacher: where the teacher is in their practice has a significant effect on what is prioritized in the transmission. The art/craft itself is always deeper than a single teacher, and thus even a master is left wondering if there are pieces of the elephant left untouched.

When I studied under Edward Maupin, a master of his craft and of teaching it, there were already a long line of sincere apprentices/students before me: Carol Osborne-Sheets, Mela Berger, Ulla ___ (alas, Ed does not fully recall this one, even though I know she was teaching with him for a period of a few years), and Jeff Linn. Carol has become well recognized in the field of massage, both for her development of deep-tissue (with a focus on connective tissue) and passive joint movement blends as well as maternity massage trainings. Mela, a dancer by background, has created her own school in the Caribbean and continues to teach Structural Integration. While Ulla has disappeared from the scene, Jeff Linn went on to teach at the Guild with Peter and Emmet and become the historian and archivist at the Rolf Institute. I know Carol and would call her a master, and after meeting and moving with Mela as well as hearing her take on the work, I see she is a master of her craft as well. In terms of Chinese lineage this makes Ed a grandmaster: a master who has trained a master.

I personally spent many years with Ed, asking him about his path with learning and teaching the craft. I know that during Carol’s era he was focused on practicing and integrating the spiritual components of the Arica system with SI. During Mela’s time he had learned finally a movement form that allowed SI to make sense to him in an embodied sense from Oscar Aguado. During Jeff’s time he set about writing down what he taught in his first manual, The Structural Metaphor, and had begun reaching out to other schools to remain in touch with their work. I began to apprentice with Ed during a time of great expansion in his work, when he undertook to open a “college of somatics.” He was not only training me in SI in his office and allowing me to assist in the SI classes, he asked me join him in “the project”, to go through a curriculum as the pilot student in his BA and MA program for somatic studies and somatic psychology. It was a wonderfully creative time lasting many years. During this period, I saw Ed’s touch become considerably softer and more internal as his focus on energetics sharpened. Between 1998 and 2003 he developed more definitive manuals for his approach to somatic psychology (The Body Epiphany) and Structural Integration (A Dynamic Relationship to Gravity, Vols. I and II; I wrote half of the second volume). We travelled and taught internationally and I developed the curriculum and became a primary in the SI program for our home school, IPSB. I feel blessed to have witnessed Ed in the fullness of his power and influence as a practitioner and teacher. Yet I still wonder what Ed I would have witnessed and learned had I met him 10 or 20 years earlier, how his own interest in developing the craft would have met mine then.

I know that a student learning from me some 15 years ago would have been exposed much more to my focus on using lower body leverage and the accurate delivery of pressure through the transfer of weight in effecting connective tissue change. Today I would be communicating significantly more about continuum mechanics and the histological composition of different fascial categories and their expected deformation response to applied pressure. I continue to develop new manual techniques every month; they certainly wouldn’t learn the ones I have left behind over the past 15 years (which were great in themselves, I wish I had written them down more clearly). However, they would witness a diaphragm contact I apply during session 5 that I realized after reexamining the changing mechanics of the costovertebral/transverse hinges across the thoracic spine, or the current approach I take to differentiating the peroneal compartment which I only put into practice after a significant study of plantar fasciitis and the Achilles paratenon. I feel like I am clearer now than I have ever been in my focus and intention, and yet it may be the someone who needed to meet me then, would have gained much less from me now.

These are the thoughts that surrounded my meeting with Mela, as did the realization that what we learn in the practice of SI is more than a goal or a theory of the body or a set of techniques. As students of no matter what era, we can find profound inspiration in finding a teacher where similar passions for learning meet with our own. I felt the same feeling on meeting with Mela that I did when first meeting with Ed, that I was in the presence of someone who never stopped building and developing the craft, and who also had the talent for sharing it.